Making a picture contains two levels of experience. For example, when I amstanding in the LandscapeI am feeling the sun or the wind, sensing approaching rain, breathing it, smelling it. It is a physical experience that I associate with the outdoor space that I inhabit and that I am trying to represent. On the other hand, in trying to draw and make some visual explanation of my experience I am much more constrained by technical matters of tone, colour and formal relationships. I become totally preoccupied with those formal properties to the point that I forget I feel cold, or my easel is trying to blow over, or the sun is getting in my eyes. It is not a question of finding a gesture or colourful mark that will express the way I feel. I work through a subject with a particular visual interest for me and I am trying to record the elements that go to create that special interest in the simplest way I can. It is an abstract realisation, the way in which, for what may be quite a short time until the light shifts and the sensation fades, various components come together in a happy configuration of light and form. I have to try and explain it.

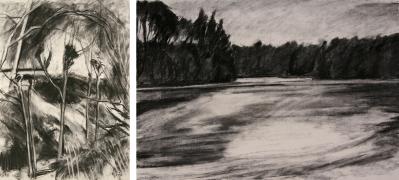

I am particularly interested in the way in which the objects or my subject matter inhabit their space. I want that space to be like a stressed three-dimensional structure. So I am more concerned about defining what isn’t there than what is. (Have a look at Degas’ drawings. You could carve the space he leaves around his figures.) It comes down to a question of structure and dynamics, more the way objects coexist, relate to one another, than their individual existence. The tighter the lines of reference are drawn between the different parts, the greater the tension which enables the communication of that original experience that I was trying to record in the first place, and the wind and weather find their own way into the drawing in spite, rather than because of, anything I do.

The weather in the north of England where I live is never predictable. The glory of the English landscape is its moody changeability. We talk of little else. We must arm ourselves daily with a wardrobe of clothing to take account of hail, storm, squall, mist and blazing sun. I sometimes take a paint pot of sand to hang from my easel and stop it blowing away.

To take account of this problem as a landscape painter I need a material with which I can complete a drawing in anything from ten minutes to two hours – well, almost complete it. I use pastels because they are a simple, uncomplicated drawing tool, and provided I limit the number of pastels to around ten I can explore the spatial shape and dynamic of my subject in quite a short time. I use kitchen paper in the same way that you would use a rubber with charcoal, as a tool to remove, spread and saturate and generally draw back into the pastel. The paper I use is 250gsm Somerset, satin smooth and with a low sizing. It holds the pastel and the surface does not interfere with the drawing. Sometimes I use a 200gsm cartridge which is harder and allows the pastel to be moved around more freely. I may have to use greasy fingers and thumbs to make the pastel lie down at some point.

I use Unison pastels exclusively, which are made nearby me in Northumberland and are ideally suited to the way I work. They come in a pinky size and in a thumb size, which is particularly good for a broad application of colour. They are quite firm but soft enough to spread so do not disintegrate at the first show of ill-temper. I can really bash them into the paper with impunity. Also they come in a fabulous range of earth colours and subtle greys, not to mention the blues and violets, and each colour has its own character and individuality.

I work by adding and removing and only at the end when I need to resolve surfaces and reinforce the overall construction do I put the kitchen paper to one side. The work may need very little doing to it back in the studio to simplify some areas and adjust the structure, but it may be several months sitting on the studio wall till I can work out where it is going wrong. I am not sure if my approach is unconventional, but what I am doing by spreading and rubbing and removing is to move the pastel about through the drawing, up and down and across, in order to make those connections that I was talking about before, so that colours and ground colours connect up with each other and I can build into the foundations of the work the angles and main structural lines of force.

By organising his paintings around the horizontal and vertical, and by laying his colours on side by side, Cézanne was able to bring the work forward to the picture plane, a lesson which informed most of 20th Century art from Matisse, to Cubism, Mondrian and onward. On the other hand I tend to build my work around the diagonals which converge and take the space back behind the picture plane. It creates a more dynamic structure giving a greater sense of instability and imminent change, which is what I am up against most of the time.

The seascape is an enduringly fascinating subject matter. It is such a simple format - if I can avoid getting unduly involved with a complicated shoreline foreground. So much happens around the horizon, that horizontal force that arbitrates the dialogue between sea and sky. That is where the interest lies for me. The whole focus of the drawing lies in the meeting of the sea and sky, and the tonal contrast along the line and the softness of that edge are critical. The planes and angles of sky, sea and shore all come together at this point

I work quickly because the light and weather do not give me much time. There are three drawings here which were done one after another between about 3.30 and 6pm one afternoon. I worked on each of them for about half an hour back in the studio making small adjustments. Sometimes I start larger (imperial) when the light is more stable in the middle of the day, and as the light starts to change more rapidly I drop down to half imperial, and then, in a late rush, quarter imperial (approximately). The last drawings may take only 20 minutes.

I don’t believe in making wild colour contrasted statements. Nor do I like moving far away from the local colour. By looking very closely there is a lot more hidden subtlety to discover in colour in the landscape. I find too that by keeping a close tonality, for example, in skies, it is possible to create a more resonant sense of space and depth. Tonally contrasted skies are often crude and unwieldy.

I never use a camera as I am trying to record the living presence of my environment. Photographs are good for details if that is what you are interested in, but they give no sense of the experience of being there. For me to make a drawing from a photo would be like trying to give personality to a corpse. The best I could do with a photo is a sort of pastel Photoshop job on it and bounce it into life with some spectacular colour and chiaroscuro – hardly more enlightening than rouging up a dead man’s cheeks. .

On another practical point - I always work standing up at an easel. I have to be able to move my arm freely and to continually step back from the picture to reassess the progress of the work at every stage. I never feel in control propping a board or a pad on my knee.

Practical tips

Concentrate on having something to say about the structure of your painting. It is often helpful to do a thorough study in black and white first so that the work has some strength and shape.

Once you have identified what you want to say, don’t let fussy detail get in the way.

Detail has to have a point. If it has no point, get rid of it.

Use as few colours as you can. This will give your work greater unity and the shape of the work will be easier to control. It will be stronger and clearer.

When in doubt simplify, simplify, simplify.

Peter Podmore –Biographical details

I first started to take an interest in painting when I was teaching English in Paris, and, having time on my hands in the middle of the day, used to go to a studio in the celebrated Rue de la Grande Chaumiere, frequented by the great French artists of the earlier part of the century, where there were models available for drawing. Eventually, after a few years teaching in England, I went to art college in Farnham, Surrey to study Fine Art. Afterwards I did some art teaching in colleges but spent more time working at home. I was interested then in a constructivist language, using very simple geometrical forms and usually black, white and wood surfaces to explore space and the paradoxes of space. Mostly they were simple wooden constructions which went flat onto the wall. I also used handmade paper which I would fold to create shapes which I would then draw on following the geometry of the folds in charcoal and conte. I showed this work around galleries in England, but also in Holland and Poland where there is a much stronger tradition of this kind of work.

In about 1993 I ran out of steam with this approach, found I was simply repeating myself, and decided to work from life. Having shared a studio with a fellow artist who had an interest in life drawing I had already dipped my toe in the water of this change of direction and started to paint and draw in the landscape. Apart from having to radically rethink my working method I also found that for the first time it was possible to sell a certain amount of work and that I was showing in a different kind of gallery. I had mostly shown in public funded spaces before, now I had to show in commercial galleries. I try to organise one man shows for myself and avoid group shows and competition exhibitions as much as possible, as I am a great believer in a body of work (if it has anything of interest to say) making a convincing argument to the viewer, and the better the work the more important this becomes. Because it is very difficult to persuade galleries to show landscape outside its own geographical region, I have mostly shown my works in Northumberland and in Newcastle where I previously had my studio until 1995.